(845) 246-6944 ·

info@ArtTimesJournal.com

Bluebeard: the Legend, the Spoof, the Two Operas

By

FRANK BEHRENS

ART TIMES November 2007

|

Many years ago,

I ran a miniseries about the Faust legend on the musical stage. The

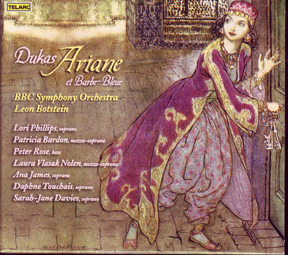

recent recording on the Telarc label of Paul Dukas’ “Ariane et Barbe-bleue”

has spurred my interest to compare it with other versions and to see

what comes out the other end.

The

original legend, possibly based on an actual nobleman who lived in the

6th-century, might have been the basis for the version by Charles Perrault

that was printed in 1697. In this version, Bluebeard’s beard was really

blue and something of a put-off to prospective brides. (No one knew

what had happened to his first three wives.) He marries the youngest

daughter of a family, goes on a trip, and leaves her with the keys to

all the rooms in his chateau, but forbids her to enter only one room.

Like

Pandora, she cannot control her curiosity. Spurred on by one of her

sisters, she opens the forbidden door and finds the bloody bodies of

the three previous wives. Back home, Bluebeard sees blood on the key

and wants to behead both sisters. However, their two brothers save them

by killing the killer, and the widow uses all his wealth to help out

her family. Happy Ending.

In

1789, Andre-Ernest-Modeste Gretry wrote an operetta on the subject called

“Raoul Barbe-bleue,” but I have not been able to find any synopsis of

the plot. (Any help from my Readers would be appreciated.)

Jacques

Offenbach did a typical spoof of the story in his “Barbe-bleue” (1866)

in which Bluebeard hands over each wife to his court chemist for poisoning.

The chemist, however, finds this an easy way to build up a personal

harem of what adds up to six charming rejects. When the master finds

out what has been going on, he decides to pair the six with six rejected

lovers of a female monarch, thus providing a Happy Ending.

Skip

now to the early 20th-century. A Hungarian composer named Bela Balazs

wrote a libretto called “Duke Bluebeard’s Castle” (or simply “Bluebeard’s

Castle” as it is more often known), and Bela Bartok turned it into a

moody musical masterpiece. The work runs under one hour and calls for

only two singers: Bluebeard and his new wife Judith. (Think Old Testament

for the obvious symbolism of the name.)

He

is showing her his dark castle, door by door. If we consider the setting

to be inside of his mind, the meaning of the rooms’ contents becomes

a bit clearer. The first houses a torture chamber (his infliction of

mental cruelty on himself and others). The second, an armory (his valor).

The third his wealth (his power). The fourth, a flower garden soaked

in blood (beauty from suffering?). The fifth, his domains that include

the entire universe (the stretch of man’s imagination?). The sixth,

a lake of tears (regrets from the past).

The

seventh and forbidden door reveals the other six wives—still alive!

He explains why he loved each of them. And having probed further than

she should have into her husband’s mind, Judith joins them as they silently

file back into the room. Thus ends the brooding psychological tale of

a bride and her husband. Read into it what moral you will.

There

are several CD recordings of the Bartok work but only one of the Dukas

versions in the current catalogue. It is conducted by Leon Botstein

and stars Lori Phillips as Ariane and Peter Rose as Barbe-bleue. While

not tuneful, it is certainly melodic and much more varied dramatically

and musically than is the Bartok version.

Here

it is Ariane’s Nurse who goads her into opening several doors, out of

which pour countless gems. In true Universal-horror-film style, the

peasants have been threatening to kill Bluebeard, whose life is saved

by his new bride at the end of Act I. Act II finds her among the other

wives, who somewhat reluctantly agree to be liberated by Ariane. In

Act III, she tries to bring back their self-esteem. When the maimed

and bloody Bluebeard is brought in by the peasants, Ariane sends them

away and cares for his wounds. But when the time comes for all the wives

to leave with her, they decide to stay behind and care for their former-husband.

Ariane leaves alone, her last words being “Adieu…be happy.”

The

price of women’s lib is loneliness? The other wives are fools? Ariane

is a fool? Actually, the two serious operatic treatments complement

each other in some abstract ways, and hearing both is a dramatic and

musical experience I can highly recommend.